Choix d'œuvres

Jupiter and Semele [Jupiter et Sémélé]

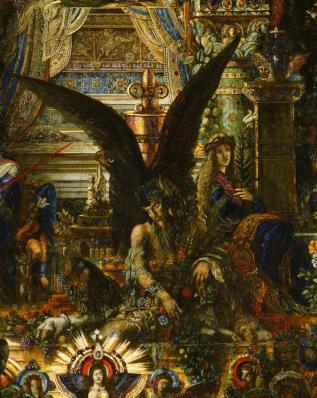

The first sketch for this painting is dated 1889, but it was only delivered to Leopold Goldschmidt, who commissioned it, in 1895. He donated it to the museum in 1903. A true synthesis of Gustave Moreau’s art, it can be regarded as his pictorial testament. It depicts the moment when Semele – daughter of Harmonia and Cadmos the founder of Thebes –is struck by lightning, overwhelmed by the vision of Jupiter transfigured, revealed in all his glory.

Semele had listened to the words of the perfidious Juno, his legitimate wife. She, in a jealous rage, had taken on the features of Beroe, Semele’s old nursemaid, in order to gain her confidence, and suggested that Semele demand this metamorphosis from her lover knowing it would be fatal for a mere mortal. The winged figure hiding its eyes is, for Moreau: “The genius of terrestrial love, the genius with the goat hooves”. However it is sometimes identified as Bacchus, fruit of the tragic union of the god and Semele. Bacchus, torn early from the maternal womb, according to the myth, was quickly sewn into his father’s thigh and developed there into a fully-grown baby.

Around the throne, hidden by the vegetation, a number of figures become aware of a supraterrestrial life. Breaking with the traditional iconography, Moreau depicts the god as beardless, and by placing a lyre in his hands, the usual attribute of Apollo or Orpheus, makes him into a poet god. At the base of the throne are two allegories: Death, which has just finished its work, holds a bloodied sword, and Sorrow, crowned with thorns like Christ, holds a lily, a symbol of purity. For the painter, these “form the tragic basis of human life”. Near these two figures we can see, on the one side, the Eagle with outstretched wings, Jupiter’s attribute; on the other, Pan, the god with cloven hooves, on whose thighs a multitude of small creatures endeavour to free themselves from their worldly bonds.

A telluric divinity, Pan forms a link between the Heavens and Hell where Hecate reigns, the Night. She appears at the bottom of the painting, with a crescent moon on her head. Near her “is piled the sombre phalanx of the monsters of Erebus, hybrid beings […] that must still wait for life in the light, creatures of shadow and mystery, indecipherable enigmas of darkness.” The two sphinxes, at the bottom of the painting, symbolise the past and the future, and are the guardians of this diabolical flock. Moving away from the lower part of the painting, its vertical development should be construed as the path the soul must take towards increasingly spiritual regions.

![Jupiter and Semele [Jupiter et Sémélé]](/sites/moreau/files/2020-11/Cat.91%20Jupiter%20et%20S%C3%A9m%C3%A9l%C3%A9.jpg)

![Jupiter and Semele [Jupiter et Sémélé]](/sites/moreau/files/2020-11/Cat.91%20D%C3%A9tail%201%20Jupiter%20et%20S%C3%A9m%C3%A9l%C3%A9_0.jpg)

![Jupiter and Semele [Jupiter et Sémélé]](/sites/moreau/files/2020-11/Cat.91%20D%C3%A9tail%202%20Jupiter%20et%20S%C3%A9m%C3%A9l%C3%A9.jpg)